Trigger Finger/Thumb

Trigger thumb and trigger finger

Trigger thumb/finger is a common problem in all age groups. In children, the thumb is commonly affected, trigger fingers are very rare. In adults, triggering of digits is more common. Adult triggering is more common in diabetes.

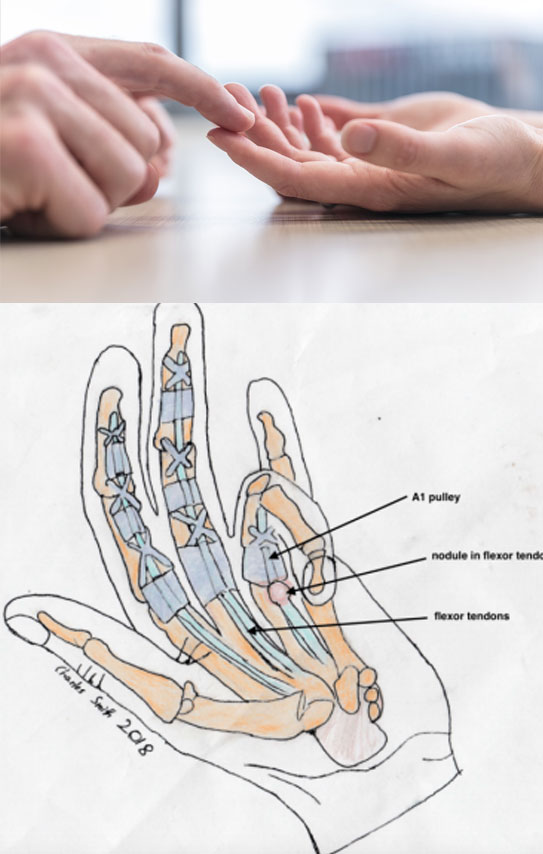

Anatomy

The underlying problem involves the flexor tendon mechanism, on the palmar side of the thumb or digit. The flexor tendons are slung against the skeleton by a series of “pulleys”, which act like the runners on a fishing rod. The pulleys are very snugly fitted around the tendons.

Cause

In trigger finger/thumb, the pulleys thicken, and begin to rub on the tendon, which develops a lump in response, rather like a callus develops in the skin. Eventually, the lump becomes too large to freely glide under the pulley. The patient will initially experience snapping, which is often painful. The pain is often felt around the PIPJ, the second joint from the fingertip. Eventually, the digit may become “locked” usually in a flexed position, when the lump can no longer pass beneath the pulley (see diagram).

Diagnosis

The diagnosis can usually be made on physical examination, the lump can be felt and the location of the snapping confirmed. Sometimes with early triggering, the snapping is intermittent and the lump is hard to feel. A carefully performed ultrasound is helpful in this circumstance to confirm the diagnosis, though this must be performed by a radiologist with an interest in and an understanding of hand problems.

The anatomy of a trigger finger

Wound for a trigger finger release

Treatment

Splints are typically worn to prevent flexion of the digits, which stops the tendon nodule from snapping under the pulley. This may limit symptoms at night time especially. Splinting probably does not change the evolution of the condition.

Corticosteroid injections may have a beneficial effect on the condition, roughly half the time. Will they work for you? It is impossible to predict this accurately. If you have the luxury of time and are keen to avoid surgery, then it is something to try. But no more than twice. If the condition persists after two injections, it is unlikely to respond to more. The side effects are rare, though they can be serious, such as flexor sheath infection and skin thinning.

Surgery is the most effective treatment for this condition. My preference is to perform the surgery in the ideal conditions of the operating room but under local anesthetic. The surgery is “minor”, a small skin incision is made over the pulley, which is cut. The patient is then asked to flex the digit, to ensure that there is no further snapping. The skin is closed with a few simple, fine, nylon sutures, which remain in the palm for 12-14 days. It is recommended that the wound be kept relatively dry until the sutures are removed. This is because when the palmar skin gets full of water, it gets soft, and the sutures can “cheese wire” through the skin. Otherwise, the hand can be used as normal for most activities.

The main side effect of the surgery is local tenderness and thickening, which is transient. Recurrent triggering is very rare. Infection is also a rare complication.