Nerve Injuries

Anatomy:

Peripheral nerves are like the electrical wiring system of the body. They connect receptors to the spinal cord, and the spinal cord to muscles. Nerves can be thought of as sensory (carry feeling), motor (connect to muscles) or mixed (do both).

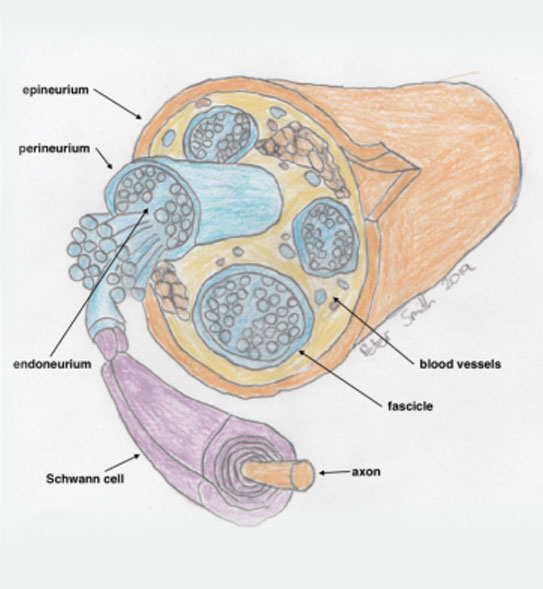

Nerves are made up of axons (nerve cells) bound together by their supporting structures. Each axon stretches from the spinal cord to the end of the nerve’s course but is too fine to be seen with the naked eye. Axons are bundled together, surrounded by epineurium and padded by endoneurium (see diagram).

Types of injury:

Nerves can be cut, stretched, compressed, or injured in other less frequent ways. The injuries may be partial or complete to both the axons and the supporting structures. An example of a complete injury would be when a nerve trunk is completely cut, all the axons and the supporting structures are divided. An example of an incomplete injury would be a crush injury, where the outside of the nerve remains intact. On the inside, the axons may be all “in-continuity”, “partly continuous” or “discontinuous” (see diagram).

Internal anatomy of a nerve

Injury to the nerve cell (axon)

When an axon is damaged, as long as its nerve cell body is intact, it can regenerate. If the axon has been cut, then the part downstream from the injury will disappear over a number of days (Wallerian degeneration).

Upstream of the injury, the axon starts regrowing and looking for the supporting tube that it previously ran down. If the axon successfully finds the tube, it will grow down it at about 1mm per day (varies considerably) towards its target organ (sensory organ or muscle end plate). Once it finds its target organ, a function for that axon may be re-established. For sensory nerves, there is no time limit. For motor (muscular) nerves, the axon must find the motor end plate (muscle) by 18 months after the injury, or the end plate will disappear, and function cannot be regained.

Diagnosis

The story and the examination are very important in getting an idea of what might be going on with the nerve. For example, if there is a story of a sharp injury, like broken glass, and there is no function in a nerve on examination, then it is highly likely that the nerve has been lacerated, and requires surgical repair.

If the injury occurred with pressure, and there is some function in the nerve on examination, then it is likely that it will recover with observation.

Imaging, such as ultrasound or MRI has a very limited role in accurate diagnosis of nerve injuries. Occasionally it can be useful if guided by the surgeon making the assessment.

Surgery

In an acute injury, sometimes surgical exploration is required for an accurate diagnosis.

Early on after the injury, if there is a complete transaction, then accurate microsurgical repair is usually the best treatment. The axons still have to grow from the site of injury to their target organs at 1mm per day, so don’t expect an instant recovery.

Sometimes, if there is a significant injury to a section of the supporting structures, or if there is tension across the repair, then nerve grafting may be required.

Sometimes, if a motor nerve is damaged to far from the target muscle, after a direct repair, the axons may not reach the muscles prior to the 18-month deadline. In this case, a “nerve transfer” may be indicated. This means stealing motor axons from a functioning nerve and redirecting them into the injured nerve, close to the target muscle.

If there is a failure of muscle reinnervation for some reason, and there is a residual weakness, then other surgical options may be of benefit. Tendon transfer surgeries make use of expendable muscles by re-routing them into the tendons of paralyzed muscles. Other surgeries sometimes of benefit in this situation include tenodesis and joint fusion, to stabilize flail joints.