Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

The median nerve

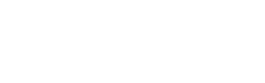

Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) is caused by pressure on the median nerve, as it passes through the “carpal tunnel” or the bony and fibrous tunnel of the wrist.

The soft, delicate median nerve is part of the nervous system, just like the brain and the spinal cord. It is specialised to transmit information from sensors in the skin to the central nervous system (CNS, the brain and spinal cord). Typically the skin of the thumb, index, middle, and half the ring finger is taken care of by the median nerve.

The median nerve also connects the CNS to some important muscles of the thumb and hand.

The carpal tunnel

The carpal tunnel is formed by the bones of the wrist, with a strap of tough ligament (transverse carpal ligament) forming the roof. The median nerve and 9 tendons pass through this space. The space is at its maximum volume when the wrist is straight, and any movement away from this position will tend to compress the nerve.

There are many medical conditions which can lead to carpal tunnel syndrome, but often there is no clear cause. When carpal tunnel syndrome occurs during or after pregnancy, it usually resolves in the short term, but sometimes splinting or steroid injection is required.

The carpal tunnel and the median nerve

Symptoms

The first symptom is intermittent tingling, often at night. The tingling becomes more frequent as the problem worsens. Numbness or loss of feeling in the fingers usually begins later. Patients often describe this as “loss of circulation” and hang their hands down at night to get the feeling back. Symptoms during the day are tingling and numbness, which are provoked by activities which require the wrist to be extended, such as driving or talking on the phone.

Later symptoms include permanent loss of feeling in the fingers and diffuse pain, which can extend all the way up the arm to the shoulder. The weakness of thumb motion occurs with severe carpal tunnel syndrome, due to wasting of the thumb muscles.

Examination

The doctor’s physical examination and sometimes tests, help differentiate carpal tunnel syndrome from other conditions which can cause almost identical symptoms. The most common of these is nerve root compression in the neck, by arthritis or by a disc prolapse.

Tests

Supportive tests are either physiological or anatomical. Physiological tests include nerve conduction studies, which look at how fast the nerve can conduct impulses at various levels. Delay at the carpal tunnel level implies a problem here, but does not specify that the problem is compression. Nerve conduction studies will remain abnormal for a number of months even after successful decompression and resolution of symptoms.

Anatomical tests look at the shape of the nerve at the carpal tunnel, and include ultrasound and MRI. If the nerve is flattened under the ligament and thicker on either side of the ligament, it implies a compressive problem.

Grading of severity

It is important for the patient and doctor to understand the severity of the nerve damage prior to commencing treatment. In more severe carpal tunnel syndrome, the nerve itself has been damaged, and even after successful decompression, it may be many months before the nerve returns to normal. It is rare that the nerve is so badly damaged that it cannot completely recover, though this does occur.

Treatment

- Splints Splints sometimes help in controlling symptoms in CTS. The carpal tunnel narrows further with any movement away from the neutral position, so the splints must keep the wrist straight. Patients may find splint helpful at nighttime, to minimise symptoms. Splints are especially useful if there is a transient cause of the carpal tunnel syndrome.

- Steroid injections Anti-inflammatory cortico-steroid preparations may decrease the swelling around the median nerve, and relieve the symptoms, though usually only temporarily. A good response to a steroid injection is the best predictor of successful relief of symptoms following surgical decompression, and the injection may sometimes be recommended if the diagnosis is uncertain.

- Open carpal tunnel release Open surgery has been commonly used and continues to be the preference of some surgeons. The carpal tunnel is accessed via an incision through the palm; the fat and palmar fascia are cut to expose the transverse carpal ligament, which is the structure to be released. The wound and then the scar is situated in the palm, which must be kept dry for 14 days. Many patients find the scar is tender, and frequently irritating, for many months.

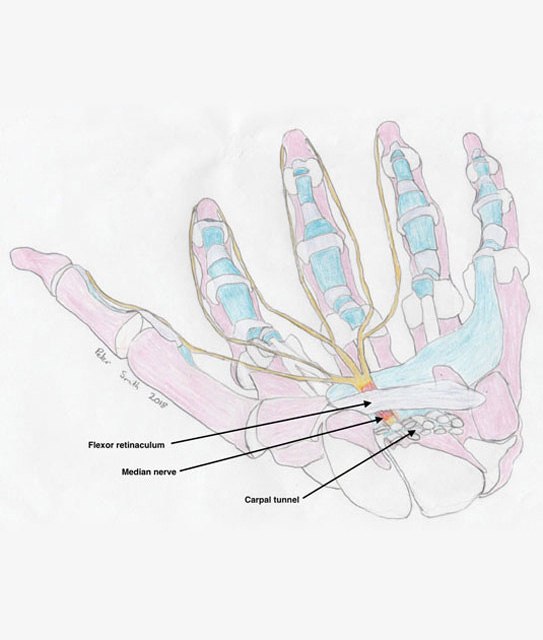

- Endoscopic carpal tunnel release ECTR is my preference for the majority of patients. Modern ECTR is safe, elegant surgery, which allows double the speed of functional recovery. The recovery of the nerve is identical to open surgery.

Left: setup for endoscopic carpal tunnel release, Right: endoscopic view of the median nerve and transverse carpal ligament

The scar is in the lower forearm and allows the endoscopic device to enter the carpal tunnel. The nerve and ligament are observed, and only the ligament is divided. The golden rule of hand surgery is “don’t see, don’t cut”, and if for some reason, perfect visibility is not achieved, then the procedure should be switched to an open release. This is extremely rare if the surgeon has been properly trained in the procedure.

Microaire ECTR system

The incision is closed with invisible absorbable sutures, and sealed with a waterproof dressing. The hand may be immediately used for light activities, such as washing, personal hygiene, eating, typing and even driving, if the patient feels safe. Most patients can return to work after 3 weeks.

Because some use is possible immediately, many patients who have both sides affected will choose to have surgery on both sides at the same time. This will significantly decrease the overall time required for recovery, compared with having surgery on one side at a time.

ECTR wounds under waterproof dressings